While the Adventist denomination is grounded in a strong biblical foundation and well-articulated church doctrines, there is also a culture to our church family. This culture makes it possible for you to feel instantly at home in any Adventist church, to casually throw out words like “vespers” and “veggie meat” and be understood, and to find friends all over the world because they know Mrs. Smith who used to attend church with Mrs. Maxwell who used to be your mother’s nursing school professor.

But is there really a common cultural thread that runs through all of our collective Adventist experiences?

There is no question that religious organizations can also function as cultural systems.1 More than just doctrines, creeds, or other external commitments to a higher Being, religion can serve as a cultural unifier within communities, guiding members’ actions, expressions, and social norms. While studies have been conducted on doctrine, very little research has been done on the culture of religion.

Thus, I sought to study Adventism in the United States in this light, recognizing that the principles of this study could be applied globally. I wanted to use Adventist culture as a variable—something that could be quantified, measured, and compared. This idea, however, rested on the concept that there is an Adventist culture that is cohesive and consistent, an idea rejected by some who argue that we were too diverse. I, however, remained convinced that a particular Adventist culture spanned the United States and that certain traditions and values crossed geographic lines.

First Stage

I patterned the first stage of the study after the work of cultural anthropologist William Dressler.2 Through friends, colleagues, and social media, I collected 61 self-described “active, involved members of an Adventist church” who equally represented the eight unions included in this study: Atlantic (AUC), Columbia (CUC), Lake (LUC), Mid-America (MAUC), North Pacific (NPUC), Pacific (PUC), Southern (SUC), and Southwestern (SWUC).

I met with each union either in person, on the phone, or by videoconference, and gave them the same prompt: Imagine a traditional Seventh-day Adventist that lives according to the prescribed Adventist culture. What behavior or characteristics would you expect to see in this individual? I then asked the participants to list everything that came to mind with the term Adventist culture, including their knowledge of the community and not of themselves personally.3

Most respondents had an easy time and, as they rattled off traits and characteristics, my notetaking turned into a speed-typing test.

Vindication

It is difficult to articulate the deep sense of belonging and familiarity that came across in these conversations with complete strangers. Out of this free-listing exercise emerged countless stories of Adventist culture: meeting a future spouse at Bible camp, eating haystack at every vespers,4 knowing that a list of “Sabbath chores” was waiting when one came home from school on Friday, soaking beans on Thursday so that they could be cooked on Friday morning and ready for Sabbath supper that evening—the list goes on and on. Though different in detail and context, the stories had many commonalities and shared themes. Faint glimpses of the framework, the underpinnings, the shape of Seventh-day Adventist culture began to emerge ever so slightly from these conversations, and the prospect of defining and quantifying culture started to seem feasible.

After the final interview, I examined all my notes from each respondent for frequency and salience. I felt no small amount of satisfaction as I carefully went down each response because here was my counter to those naysayers. Regardless of where these people lived, were raised, or became a baptized member of the Adventist Church, the data were overwhelmingly similar: There was a core set of responses that, from person to person, was almost identical, and to me—born and raised in the Adventist Church—deeply familiar. This dealt with Sabbath preparation and activity, diet and lifestyle, dress, evangelism, education, and even the propensity to play musical instruments.

Consolidating and reducing the lists of responses based on redundancy and overlap eventually whittled down the total number of statements to 27. Statements included these three beliefs and practices:

- Believes that the body is a temple of God and refrains from eating or drinking harmful substances

- Prepares for and celebrates the beginning of Sabbath on Friday at sundown

- Is almost exclusively immersed in an Adventist community, both personally and professionally

Second stage

With this list, I then proceeded to the next stage. I procured a snowball sample of 63 individuals—again, all self-described as active, involved members of an Adventist church and equally representing all eight unions. After hearing about the study summary, the respondents were instructed to rank all 27 items, beginning with what would be most important to a traditional Seventh-day Adventist in good standing. The purpose of this second step was to assess the degree of agreement, or consensus, among these items that had been identified in the first phase as being key elements in the culture of Adventism.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Figure 3.

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Figure 6.

Figure 7.

At this stage, research indicated that, indeed, a shared set of cultural knowledge exists within the population of Seventh-day Adventist church members in the USA. In other words, with this magical number in hand, the validation of a cultural domain was confirmed.

At the beginning of this journey, I had wanted to use Adventist culture as a variable—which meant that I needed some sort of scale with which I could measure it. I now had it. The “cultural key” produced from this domain can be held up to any other Seventh-day Adventist church member in the USA to gauge their level of Adventist-ness, so to speak.

Moving forward, I developed a survey that was distributed in the summer of 2018, eventually resulting in over 1,000 responses.

The survey was divided into three main parts—Adventist doctrine (which included questions such as belief in a literal six-day Creation), general religiosity (which included questions such as the number of times a week one participated in a church service or activity), and Adventist culture. The portion on Adventist culture included 14 questions derived from the ranking process. Participants were asked to list the most salient trait/behavior/characteristic of a traditional Seventh-day Adventist down to the least salient.

Conversation

By far, the most interesting part of my study—beyond the data analyses and chapter write-ups and literature review—were the conversations that I had along the way with varied Adventists. In the busiest part of my data collection stage, I was interviewing anywhere from six to nine people a day. I caught teachers between classes, stay-at-home moms in the wee hours of the morning before their children woke up, business executives after board meetings, and one musician during a short break at a recording gig.

So while the thrust of my research sought to establish a relationship between denominational culture and school choice, I gleaned many takeaways from these conversations that pertained to the Seventh-day Adventist Church.

1. We are family

We are a very closely connected group of people. One interviewee told me an incredible story that illustrates this best. He recalled that many years ago, he struck up a conversation with men in a New York airport and, after a stilted conversation in broken English, learned that they were stranded with little money and no idea how they were going to get to their end destination: California. He made a snap decision to bring the two travelers home with him, assuring them that he would do what he could to help. As his newfound guests showered and rested in his home, he rang his pastor. One call led to another, and they soon had the men on their way to a neighboring Adventist church. And so it went—one church member would connect with a fellow Adventist friend in the next city or state over, arrangements would be made, and the two travelers would be graciously welcomed into a new home, with each exchange inching them closer to their destination. The interviewee chuckled as he recalled the situation. “Believe it or not, those two young men made their way across the country, moving from one Adventist home to another.”

There is something profound, moving, and immensely valuable to belonging to a community of believers who embrace visitors with open arms and homes, who truly make people feel like family.

2. We are different

Though part of a family, we are certainly not all the same. The first part of my research set out to establish the similarities Adventists have—this shared culture—but the resulting data also revealed significant differences within the Adventist Church in the United States.

One question, for instance, asked for a response to the statement: “The Seventh-day Adventist Church is God’s true church.” The following figure displays the percentages for those who answered Strongly Agree or Agree. The data indicate that the Pacific Union Conference (40.9 percent) and Lake Union Conference (41.8 percent) had the lowest percentages of respondents who either agreed or strongly agreed with that statement.

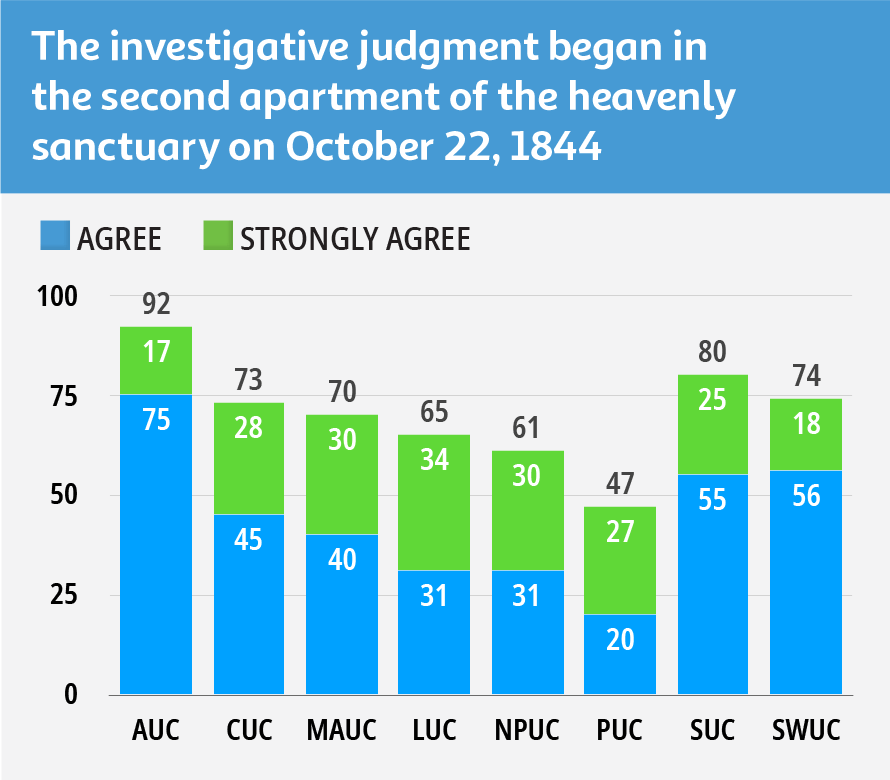

Another area in which Adventists in the USA seem to have a large dissonance in beliefs pertains to the investigative judgment.

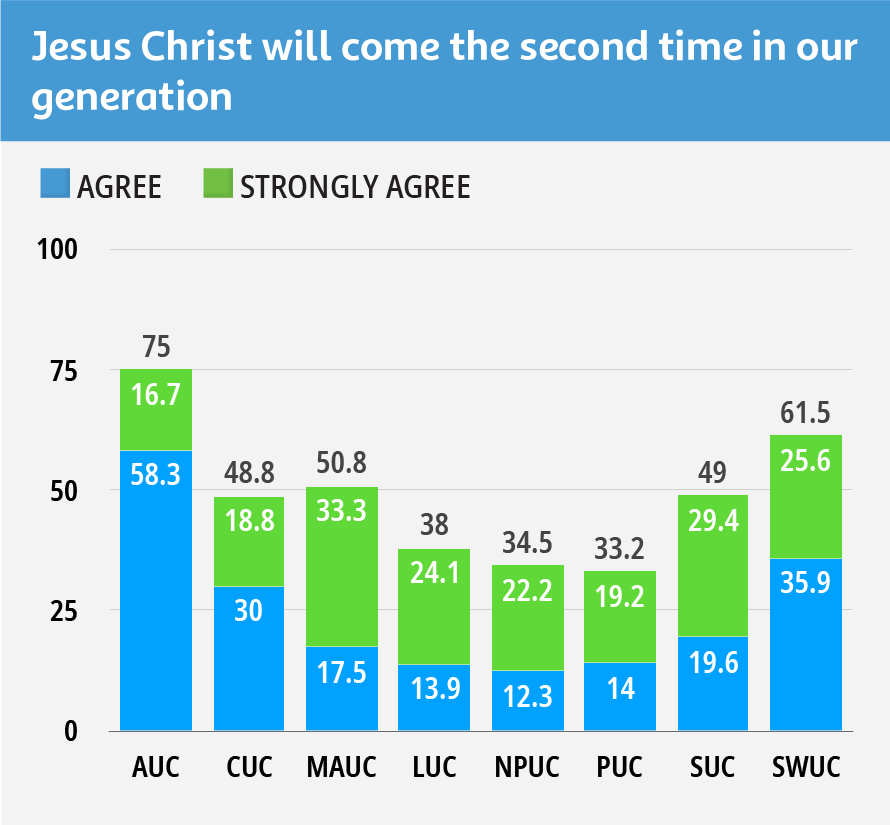

Our name, Seventh-day Adventist, references our church’s belief in the coming advent of Christ. This is arguably one of the most foundational convictions in the church—a view that set apart early Adventists from other Christian denominations in the late 1800s. It is interesting to note how that opinion is held today among Adventists across the unions.

3. We are the same

Despite these disparities, however, there are clearly beliefs that do ring true from Maine to South Dakota to California. Adventists in all parts of the USA have similarities that belie gender, age, or regional differences.

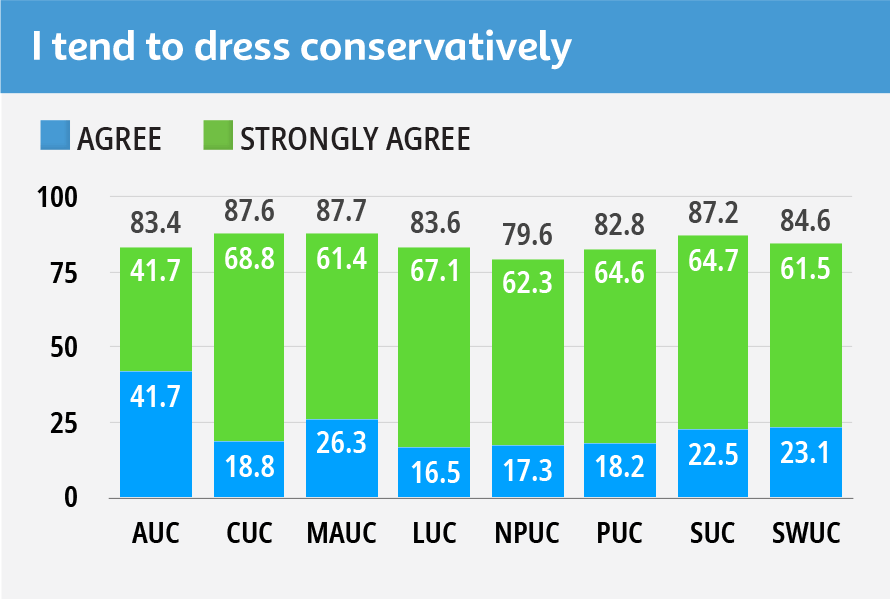

To begin with, while we may not all look the same, apparently, many of us have a fairly conservative wardrobe. The following figure demonstrates only an 11.1 percent spread between MAUC (87.7 percent) and NPUC (79.6 percent).

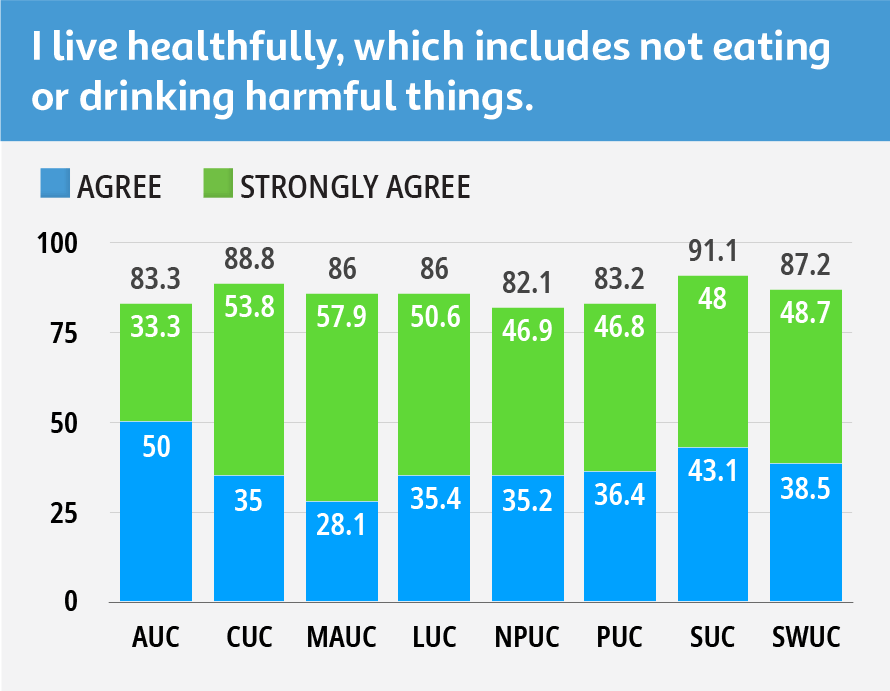

One of the bedrocks of the Adventist Church is its health message. This continues to be a stronghold, as evidenced in the following figure.

In addition to lifestyle issues, such as dress and diet, Adventists in the USA are also remarkably similar in core foundational ways as well, as seen in the next figure.

And finally, with only a four-point spread, almost all Adventists in America seem to try to live according to biblical principles.

A shared culture

As a lifelong member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, I was fascinated by the data, which provided empirical evidence to my anecdotal thoughts and feelings about our church. These general principles can be taken and applied around the world. The establishment of a shared culture within the Seventh-day Adventist Church in the United States could not only provide a springboard to countless other studies within our worldwide denomination but also shed some light on the issues that bind us together as a global family and on the issues that are not as relevant in today’s context.

Locally, take some time to study the cultural foundations in your church. How can this information guide you as you choose sermon topics? How can it strengthen the ministry choices for your congregation? Be creative, innovative, and open to new ideas as the Holy Spirit leads.

Globally, given the current religious climate in the worldwide Seventh-day Adventist Church, it might be a worthwhile endeavor for church administration to take a close look at the cultural underpinnings that sustain, motivate, and challenge our community of believers.

- Vassilis Saroglou and Adam B. Cohen, “Psychology of Culture and Religion: Introduction to the JCCP Special Issue,” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 42, no. 8 (2011): 1309–1319; Leslie Stevenson, “Religion and Cultural Identity,” Theology 101, no. 801 (May 1, 1998): 172–179.

- William W. Dressler, Culture and the Individual: Theory and Method of Cultural Consonance (New York, NY: Routledge, 2017).

- Dressler, Culture and the Individual.

- Wikipedia, s.v. “Haystack (food)," last modified January 10, 2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haystack_(food).